Blog

2014 Play it Again Conference report

On the 19th and 20th June, 2014, the Play It Again team welcomed a fabulously diverse group of scholars and practitioners to Melbourne’s Australian Centre for the Moving Image for the Born Digital and Cultural Heritage conference. In attendance were Humanities and Computer Science researchers, lawyers, archivists, conservators, librarians, game and net.art preservationists, game developers, and a bunch of interesting others besides. Lively and convivial, with wonderful keynotes from Henry Lowood and Anne Laforet, the event saw many productive lines of inquiry opened up and intersections explored.

Cataloguing video/computer games – pitfalls for new players

The issues for collection managers around games cataloguing are difficult and that may well be why we find 30 years on, the institutional collection and cataloguing of this material is somewhat limited. Similar to the new challenges of ‘Time-Based Media’ cataloguing we find ourselves with the complexities of hardware, software, documentation, versions, platforms, social memory, secondary resource material ….and the box it came in. Play It Again with its emphasis on preserving games of the 1980s, and for us particularly, Australian material, provides the Australian Centre for the moving Image (ACMI) the opportunity to work with academics and industry practitioners in refining our cataloguing work.

The William A. Higinbotham Game Studies Collection

The William A. Higinbotham Game Studies Collection (WHGSC) at Stony Brook University is dedicated to documenting the material culture of screen-based game media in general and in specific, collecting and preserving the texts, ephemera, and artifacts that document the history of a 1958 computer simulation designed by Higinbotham that, over the years, has become known as Tennis for Two. The collection is managed and curated by Head of Special Collections and University Archives, and University Archivist, Kristen J. Nyitray, and Associate Professor of Culture and Technology, Raiford Guins.

The Collection of the Computerspielemuseum

The history of the collection began when the museum was founded in 1996 by purchasing video game consoles and complementary accessories at auctions and car boot sales. Afterwards it was mainly focused on acquisitions for special exhibitions contributing to a continuously growing inventory of both software and hardware. Since the opening of the museum in early 1997, however, generous donations from many people have become the most important source for our ever-increasing collection.

Curators speak about their collections

The curation of videogames, their collection and preservation creates new challenges for the Museum. In 2002, Stanford curator of History of Science and Technology and Film and Media collections Henry Lowood called for new institutional and curatorial models capable of addressing videogames. Yet in a 2011 survey on the state of Digital Preservation, authored by Barwick et al reflected that most heritage institutions remain locked into a traditional object based understanding of collecting, and still do not have policies capable of supporting digital artefacts. There are however a number of organisations dedicated to collecting videogames and although they share a purpose in ensuring the preservation of these significant cultural artefacts their curatorial agendas are not identical but reflect the overall philosophies of the institution.

Game Preservation at the New Zealand Film Archive: A New Venture

The New Zealand Film Archive has been aware of the ‘institutional gap’ in this country for several years, with regard to the lack of representation of video games & early computer games within national cultural collections. We are wanting to acquire working examples of software and hardware across the range of formats and platforms that represent the variety that was available and played on amongst the NZ fan communities.

Law and the game cloners

Most early computer games are still protected by copyright and therefore they cannot be archived or made available online (even for not-for-profit purposes like the PlayitAgain project) without the consent of their copyright owners.

However copyright protection will not necessarily protect computer games from game cloners, who base their activities on the fundamental principle that copyright law has never protected an idea; it only protects the expression of an idea. If you are wondering what that means, then you are in good company!

“Abandonware”: A separate category to orphan works?

Many copyright works – especially books – have a potentially lengthy commercial lifespan. Of course, longevity does not necessarily equate to commercial success, but the longer a work’s ‘shelf life’, the better the prospects for the owner. Strangely enough, a...

Orphan Works circa 2014

Absent a legal solution for the orphan games, archivists have to balance the risks. On the one hand, to not archive them risks their physical deterioration and loss to our cultural heritage, but does comply with copyright law. On the other hand, to digitally archive the orphan games will preserve them for cultural heritage but there is a risk (maybe quite small but you can never be sure!) that the copyright owner might appear and instigate legal proceedings for copyright infringement.

The law – is it an ass?

During April this blog will focus on the legal environment for computer games of the 1980s. This post explains why many early computer games are “orphan works”. (An orphan work is a work which is protected by copyright, but whose rights-owner, or owners, cannot be identified and/or located.) Orphan works cannot be used for purposes which are protected by copyright.

Challenge Chamber

Showcasing gaming achievement was important for many game fans. Home computer fans had no public leader boards like those enjoyed in the arcades but magazines once more came to the rescue of Australian micro computer gamers. Each month with the pages of the Australian edition of PC Games, gamers were invited to send their high scores in ‘Challenge Chamber’.

Adventure Fans, Clubs and Help Columns

Help columns were a regular feature of computer magazine in the 1980s. As Adventure games were perhaps the most challenging games to play frequently leaving players stuck and unable to progress the Adventure help guru was a must for most game publications. The popularity of “The Hobbit” and the challenges of the Megler’s world and puzzles and the possibilities of Mitchell’s parser saw many column inches dedicated to the game.

Home Coder: Lost Treasure Recovered

Forgotten what amused your 12 year old self? Rediscover the pleasure of school boy gags and code with this lost game of the 1980s. Matthew Hall‘s Microbee adventure game the “Jewels of Sancara Island” had survived the last thirty or so years as a Turbo Pascal...

Ruminations On “The Hobbit” Fandom

In the last year of a Bachelor’s degree in Science at Melbourne University in 1981, Phil and I were hired by Fred Milgrom as part-time programmers to write “the best adventure game ever”. Based on the game’s commercial success and feedback from fandom still rolling in three decades later, we succeeded in doing so: possibly the best-selling text adventure of all time.

Fans, Fan Communities and Game Culture

Over the next few weeks, our theme focus is on game fans and fan communities. Fans have had a significant role to play in taking the initiative to document and preserve videogames – the software, the hardware they were played on, and the memories and experiences of first playing them. Game fans have understood the cultural value of videogames long before universities and museums began addressing this issue. Operating outside institutional structures, fans have drawn on the combined knowledge of large communities to build a history of gaming that’s alive and dynamic and which continues to grow.

How I got started in games – Matthew Hall – Klicktock

I started making games when I was 8. I got a Commodore 64 for my birthday. And I got one game, which was a game called “The Pit” – it’s rather obscure and it’s really shit – and the other thing I got, of course, was a manual. And so the game I finished very quickly, and then I had nothing else to do so I dove straight into the manual.

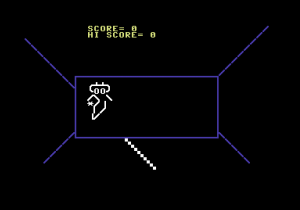

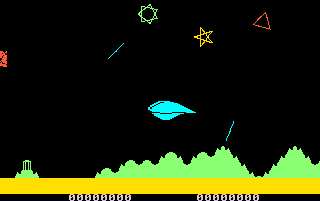

Part 3: 1980s Home Brew – The Games… Carl Muller shares his remembrance of home coding

As a teenager I loved the 1980s animated TV series Smurfs, based on the adorable 1950s comic characters. When I got a Commodore 64 I thought “with the power of sprites, surely I could create a game based on Smurfs?” and so for three months in early 1985 I tried to prove to myself that I could.

Part 2: 1980s Home Brew – Keeping up with the Commodore with Carl Muller

In Part 2 Carl tells us about finally getting his own computer, joining the local computer club and in how his interest in games design inspired him to learn Assembly language and dissemble games studying the works of UK designer Jeff (Yak) Minter.