by Stephanie Harkin

IR Gurus’ Andrew Niere shares insights into Australia’s homegrown equestrian games.

By the 1990s, games were predominately designed with young male players in mind, featuring macho-adrenaline themes like violence, guns, and military simulations. Having never made a video game before, childhood friends Craig Laughton and Andrew Niere decided to do something different from other Australian studios by developing a horse riding game for girls.

Riding Star (1998)

Niere came from an engineering degree but describes his long-time interest in creative projects. Laughton came from a commerce and law background, and so brought an “entrepreneurial flair” to Niere’s “creative flair.” Part of the inspiration for developing an equestrian game was Laughton’s recognition of a market gap. But the idea was more so inspired by Laughton’s younger sister. As Niere explains, “[Laughton’s] younger sister does pony club and when it’s raining it’s called off and she comes home and does nothing. Wouldn’t it be great if she could come home and do pony club as a game? That was the genesis for this conversation that probably a year later saw us get some funding and partnership with a local games company to start something.”

That funding came from Cinemedia (now VicScreen), who granted the pair around $110,000 to develop their first equestrian game, Riding Star, which would be released in 1998. Laughton and Niere partnered with Melbourne-based studio Blue Tongue Entertainment who offered technical expertise and “their wisdom of having made a game.”

The Riding Star team however was modest. Niere recalls, “I remember going and buying a computer and turning up at their office with a computer under my arm. And I think we had an artist and a programmer assigned and then me sort of producing. Really small initiative.” Niere explains that the Blue Tongue staff handled the technical side of development, like coding and art, which Niere learned on the job. It was an early model of a pay for hire for services arrangement.

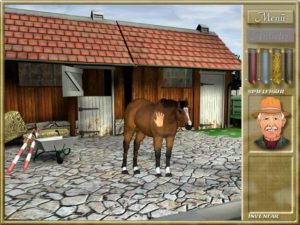

Laughton and Niere meanwhile were in charge of managing partnerships and distribution. A key connection they made was with Geoff Sinclair of Equestrian Australia who opened the door for Laughton and Niere to meet the people behind pony club to international equestrian events. “We went and met the people that lay the courses and made these rules to help us understand what this world looked like.” Niere explains the degree of research undertaken to capture the realities of the equestrian world. “We wanted to make it believable.” This included detailed attention to grooming, feeding, and the correct procedures for taking care of a sick horse—which would be a plot point in Riding Star. “We went to stores to look at equipment and out in fields to record horses hooves and watch videos of competitions to understand and analyse gaits of horses and movements.” They sought to faithfully simulate the disciplines of horse riding too, from dressage, to show jumping, to cross country.

When completed, Riding Star ended up following a 10–12 hour journey set in a Yorkshire-inspired village (with Melbourne actors cast to voice the parts). It featured 2D isometric views with some 3D elements and involved participating in competitions and conducting care and maintenance for your horse.

While Niere describes his excitement for the game, he remembers attending E3 (the Electronic Entertainment Expo) and not experiencing that shared excitement among publishers: “I don’t know if they got it at the time.” On release, Riding Star was entirely self-published.

Equestrian Retailers

When it came to distribution, Sinclair was a valuable connection to Laughton and Niere as he also held retail outlet connections. Generally girls’ games at the time were sold in the toy aisle rather than in the software section or in gaming stores. Part of this had to do with gaming’s already deeply entrenched associations with boyhood that was likely to discourage girls—and the parents of girls—to shop in these sections. In an unusual but brilliantly logical distribution strategy, Riding Star was sold in saddleries and equestrian stores. This resulted in an unexpected audience emerging.

While young tween girls were their key audience in mind, a significant number of their players ended up being middle-aged women buying Riding Star from equestrian stores. “For them to go into an equestrian store and everything’s hundreds of dollars and have a game for $50 dollars or something like that — it was kind of running off the shelves.”

The degree of research that went into the game evidently struck a chord with horse riding enthusiasts, as Riding Star functioned much like any faithful sporting simulator.

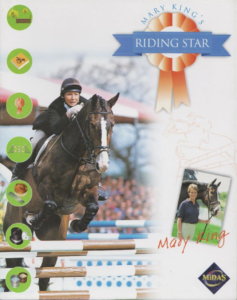

Going International with Mary King’s Riding Star (1999)

Interest in Riding Star eventually led to a collaboration with UK publisher Midas Interactive Entertainment. The game was rebranded to Mary King’s Riding Star, named after the famous British professional rider. Based in the UK, Midas had experience and access to translating and localisation channels across Europe. The game ended up being attached to several international equestrian champions through this translation process, including Ulrich Kirchhoff for the German translation, Anky van Grunsven for the Dutch, Alexandra Ledermann for the French, and ‘Lussan’ Nathorst for the Swedish.

Midas Interactive also wanted to see the game ported to the PlayStation. Laughton and Niere moved to another Melbourne-based studio, Tantalus, for the porting process. Niere reflects on this time: “The desire to be on Playstation meant that we had to go and find someone that had PlayStation experience … the programmer and I from Blue Tongue then went and moved to Tantalus … he and I were in the back corner working for I don’t know 6 or 8 months on converting … I think maybe the UK producer sent us a PlayStation dev kit or maybe Tantalus had one at the time. … but [we were] largely doing all the localisation assets and all the changing artwork from a PC version to a PlayStation version ourselves.” While Midas sent them translated scripts, Niere recalls researching the intricacies of localising different international rules to be applied to the art assets, like the winning colour being blue in Australia and parts of the UK, but red in America.

The Next Chapter: Licensing Acquisitions in Equestriad 2001 and The Saddle Club: Willowbrook Stables

As technologies shifted, elements of Riding Star would eventually be converted from isometric to 3D for the game Equestriad (ported recently to mobile by Australian studio GoGallop in 2020). Niere and Laughton, now as IR Gurus, stayed on with Tantalus but had a much bigger team. “Again it was this partnership where we were running the idea and the concept and then they were bringing their skill in terms of creating the equestrian arenas and the mechanics and using their technology.”

Around this time, and through their connections with Sinclair of Equestrian Australia, Laughton and Niere attained the license to major equestrian events; “the equivalent of the sort of grand slam tennis.” This coincided with the Sydney Olympics in 2000, and the course designer of the Olympic equestrian challenge ended up designing a course for Equestriad. The team also brought on famous commentators for the game. “We got them to write scripts and do all the recording with them. So it was really bringing all that glamour and all that excitement and prestige … into this game. So that was a real blast to recreate that.”

Another licensing deal came with the Australian horse riding tv series Saddle Club, an immensely popular series among tween and teen girls. While franchise tie-ins often only involved access to an IP, the making of Saddle Club: Willowbrook Stable, released in 2002, involved direct collaboration with the show’s production. “[We] met the producers and went to the sets of the TV show and kind of skinned our game as the Saddle Club, got their actors to re-record scripts and everything.”

Like the selling of the Riding Star games in equestrian stores, Niere recalls Saddle Club: Willowbrook Stable being sold in ABC shops alongside the series.

Making a Horse Riding Game

Niere’s reflections are fond and passionate. This wasn’t a case of a studio having little choice but to take on gendered shovelware to keep the lights on. IR Gurus was founded on the desire to make a game for Laughton’s younger sister—a girl who loved horses.

When asked whether the broader development team were responsive to the content, Niere explains that it was “predominately young men working in that space at the time [who were] passionate about the challenge[s].” He explains for instance that Equestriad involved a 4km open world. “I don’t think we really had open worlds in those days so they were using all their best technology to create boundary boxes and channels and hills and trees and visibility. I got the impression that everyone was dedicated and happy, I don’t think anyone was like oh my god I gotta work on this stupid thing.”

When reflecting on working alongside teams making traditional games, Niere remarks “we were the odd people out with this kind of wacky concept.” But this comment attests to their innovation and valuation of an audience that was immense, and yet invisible to the wider gaming industry.

Thank you for this article!! I run a website called The Mane Quest where I investigate the development and history of horse games (and review/analyze them). It’s always wonderful to see other outlets diving into similar topics and bringing interesting new tidbits about the history of this niche to light.