Melbourne House and Beam Software Director Alfred Milgrom sees “Vast cultural, societal difference in what consumers wanted from electronic games” between the mass markets for games in American and UK in the early days.

“American consumers were happy to pay for expensive cartridges that you just plug in” says Milgom. The US was characterised by the Atari 2600, a games console, a locked down hardware system that plugged into the television and used a joystick interface. He asserts “they did not want to know how it worked or what it did, they just wanted to play the game”

In contrast, the UK market was defined by people who also wanted to play with their systems, according to Milgrom. They favoured the highly modifiable local brands such as Sinclair and they weren’t happy just to drive their machines. They wanted to know what was under the hood.

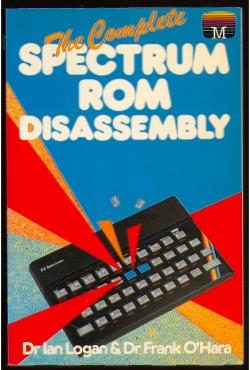

Melbourne House profited from this DIY culture. One of their best sellers was a highly technical title focused on the Spectrum’s Rom Disassembly language. Other Melbourne House books for the Spectrum offered guides to the in-and-outs of its circuit diagrams, writing in machine language and making clones of your favourite games such as “Star Wars”, “Lunar Lander” and “Adventure”.

Whilst games were part of the appeal for users of the early microcomputers, the pleasures of knowledge and tinkering were also obviously important.

So what created such a cultural divide? Milgrom opines “..the UK is pretty miserable …I mean the economy wasn’t great and the weather was miserable and people were sitting at home and so they would tinker with what they had.”

The North American market experienced its famous crash around 1983. US consumers lost faith in a market over-saturated with disappointing product and just stopped buying electronic games. However this North American experience did not affect all games markets and during the years 1982 – 1985 the home computer games market in the UK and Europe continued to grow. Melbourne House was at this time a leading UK publisher, with Beam creating its smash hits “The Hobbit” (1982) and “Way of the Exploding Fist” (1985).

In Australia microcomputers were the preferred games machine, encouraging deeper interaction than the plug and play of consoles. But Milgrom thinks the Australia consumer sat somewhere between the US and the UK.

“I don’t think that there was that same urge ever here in Australia [to know how your computer worked], in terms of a mass approach to games or computers or anything like that. I mean Australians like to mod things and repurpose things, not necessarily what they were originally intended for. But that’s more of a sport…”

Afterword: Crashing and Cracking

As befits Milgom’s observations of the pleasures of mastering more than the game; when the US was crashing, the UK and Europe were cracking. A demoscene subculture developed around ‘cracking’ games, removing copy protection and content then leaving trace signatures and artefacts behind in the game. The early demoscene was not so much about piracy but was the arena of highly skilled programmers who enjoyed the opportunity to showcase their abilities.

References: Milgrom, Alfred, Video Interview ACMI, 28 April 2006; Milgrom, Alfred, Record Interview, 20 March 2013